New York City, NY

Marjorie Eliot’s Harlem Apartment Jazz Concerts – Going Strong in its 3rd Decade

Marjorie Eliot’s Harlem Apartment Jazz Concerts – Going Strong in its 3rd Decade

Marjorie Eliot, Bob Cunningham, and Gerald Hayes from back in the day at Parlor Entertainment – 555 Edgecombe, Apt. #3F

We wanted to tip our hat to Marjorie Eliot who started Parlor Entertainment over 3 decades ago and by all accounts hasn’t missed a Sunday since the beginning. In fact, the Covid lock-down period inspired the live streaming of these events which have grown to 3 days a week: Friday-Sunday. There can be no greater soulful experience in this day and age than spending a late afternoon in the presence of such a deeply spiritual musician and hostess.

Columbia University journalist, Morgan Desfosses, honored us with some quotes in her thorough and insightful recent article about Marjorie for The Eye. With permission, we are re-printing it here for more eyes to enjoy:

THE EYE | Harlem’s Most Intimate Venue: Jazz and Legacy in a Manhattan Living Room

December 01, 2024 Tucked into a quiet corner of Upper Manhattan is one of Harlem’s last informal jazz parlors. It’s a setting you might not expect: a small living room decked with family photographs, magazine clippings of the parlor’s performers, and 30 folding chairs facing a row of musicians. This is the living room of Marjorie Eliot, who has been hosting live jazz for audiences as large as 50 people every Sunday for the past 30 years. At 87, Eliot is slight, her frame often obscured beneath the loose, vibrant maxi dresses she wears. Her hands, though, are lean and nimble, and still appear strong from decades spent at the piano. “It started as a concert,” Eliot told me one afternoon over the phone. “I’ve written that story about how it started, who was here—because we’re talking great, great musicians.” The story of Majorie Eliot’s Parlor Entertainment is one deeply infused with the history of jazz, of the neighborhood, and even the building itself. Throughout the 20th century, Sugar Hill, located in the uppermost tip of Harlem, was the stomping ground of many of jazz’s great musicians. There were clubs with live performances, jam sessions in local dive bars, and cutting contests—the jazz equivalent to rap battles—hosted in the bustle of cramped and sweaty rent parties. It was the time of the Harlem Renaissance and the Jazz Age, when many African Americans migrated to New York City and Black culture flourished, elbowing its way into the mainstream. Those movements were driven by prolific artists and thinkers whose names many of us still recognize over a century later. Eliot’s own residence, 555 Edgecombe Ave., was home to many of those leaders, and it persisted for many decades as a base for prolific artists and musicians. “There were so many musicians in the building,” Eliot said. “They loved that this was really quite something. I mean, on the 14th floor—on the top floor—and on the 10th floor, there were artists exhibiting their work and bringing folks down to hear music.” In the decades since jazz took hold of New York City, the genre has experienced significant changes. Its listeners have gone down and aged up, and its spaces have shifted to dinner clubs and esteemed concert halls, while smaller, more intimate venues have drastically dwindled. Today, streets which once swelled to the sounds of live instruments and jukeboxes carry on like the rest of New York City—to the tune of midday car horns, children playing, and Latin music blasting from stereos. But amid these changes, the unassuming living room at Marjorie Eliot’s continues to offer what parts of the industry, and indeed Sugar Hill, has lost: an intimate space where jazz can flourish. I happened upon Eliot’s concerts at the suggestion of a colleague, which was why, on a Saturday afternoon in late May, I found myself in the lobby of 555 Edgecombe Ave., walled in by marble and Baroque-style gilt panels. The ceiling was embedded with a kaleidoscopic Tiffany skylight, stained glass arms sprawling out like a celestial body. Up the ancient elevator and around the bend of a much plainer hallway, I found what I was looking for: apartment 3F. Eliot greeted me with a delighted “Hello! Welcome!” and showed me to the living room through a long hallway lined with framed photographs of friends and bandmates. The late afternoon sun seeped in through a window to the left, casting streaks of light over the folding chairs patiently waiting to be filled. Magazine clippings on the back wall of the living room displayed headlines like “Parlor Entertainment Exclusive,” “Trombonist, Benny Powell,” and “Keep it in the Family.” Against the same wall stood an upright piano, a soprano saxophone, a flute, and a clarinet—all ready for the afternoon set. While Eliot’s full band usually consists of four to five musicians, that day it was only her and her bandmate Sedric Choukroun, a multi-instrument musician who has been playing with her since 1999. At 3 p.m., Choukroun gave Eliot a nod. “It’s time,” she said, taking her seat at the piano. Her fingers floated over the keys to the haunting, melancholic tune of Duke Ellington’s “Come Sunday.” I could see a book of sheet music in front of her, though her eyes were closed. As Choukroun picked up on the clarinet, the song took on a degree of warmth, his notes meandering in and around hers. Even seated at the back of the living room, I was close enough to hear his sharp in-breaths between notes. As the song reached its end, both musicians’ eyes remained closed, hands still on their instruments. I wondered if I should clap—it seemed almost sacrilegious to disturb the dissipating notes. It just so happened that this particular Saturday, I was the only one in attendance at Eliot’s parlor. Her shows are known to fill up, so much so that audience members often spill out into the hallway, but the band had recently expanded show times to include Fridays and Saturdays, and it appeared word had not yet gotten out. I was touched by the performance, rendered with such care for a single audience member, though it was clear it was not for my sake alone. There was a palpable connection between the musicians and something ephemeral I couldn’t put my finger on. Yes, the music of course, but it felt deeper than that. When Eliot and I got to talking after the show, that something began to materialize. August 1993 marked the inaugural performance of what would become a 32-year run of shows that continues to this day. It took place across the street at the Morris-Jumel Mansion and was meant to honor Eliot’s son, Phillip Drears, who had passed away at age 32 due to kidney problems the previous year. “I wanted to celebrate his anniversary,” Eliot said. “I went over to the mansion, I wanted to plant a tree, but then I thought, who was gonna take care of it? And the music has always been central to our lives.” Instead of a tree, Eliot called up the directors of the mansion and asked to do a concert on the lawn. They agreed. “Come Sunday,” the first song on the set list then—and every show since—commemorated Phillip’s memory. The turnout at that first concert was astounding. Eliot estimated there were around 300 attendees: Friends and family members, as well as many tenants from the building, showed up to show their support. There were also dozens of veterans who had been bussed in by the Salvation Army, for whom Eliot would often play at hospitals and rehabilitation centers in Long Island City. People quickly began asking when the next show would be, and before long, it became a weekly event. The door was always open, letting the music escape into the halls as perhaps only a New York City residence would tolerate. Other artists and musicians in the building were completely on board, Eliot said, filling the apartment with friends and visitors they’d brought in to listen. Only once did someone complain to law enforcement. But the police loved the show: “They said, ‘You’re never going to have another problem.’” Over the years, the band has featured 35 different members, not including Eliot herself. Regular musicians have included her sons’ godfathers—big names like Benny Powell, a celebrated trombonist and long-time bandmate of Count Basie—as well as Bob Cunningham, a bassist and mentee of Dizzy Gillespie. Today, the full band consists of Sedric Choukroun, who plays woodwind and brass, Nick Mauro on trumpet, Yuma Takagi on bass, and Eliot and her son Rudel Drears on piano. Set lists feature a combination of improvisation, original compositions, and recognizable standards, like “The Girl from Ipanema.” Over time, through word of mouth and some intensive flyering, the shows began to draw a large crowd. New York City jazz tour guide Gordon Polatnick caught wind of the shows, and he instantly fell in love with Eliot’s events. “Here was a woman who had her door open to anyone who would walk in with or without a reservation,” Polatnick recalled. “And it was phenomenal, just on that level, to be in somebody’s space who had so much trust and love for her neighbors.” As home to many leaders of the Harlem Renaissance like W.E.B. Du Bois and Langston Hughes, the neighborhood of Sugar Hill was deeply involved in the cultural movement of the early 1900s that coincided with the Jazz Age and facilitated an explosion of African American art. The renaissance was about reshaping the public conception of African Americans. It embraced the use of art and literature to, as Alain LeRoy Locke, the “Father of the Harlem Renaissance,” put it, “discover and reveal the beauty which prejudice and caricature have overlaid.” Although many renaissance intellectuals critiqued jazz as a commercial corruption of Black music, the genre became one of the era’s most pivotal contributions, through which African American culture was able to enter the mainstream. In the 1920s, Harlem became the site of great advancements in the genre, and a new style of jazz piano known as the Harlem stride emerged. The style was developed at rent parties—house parties and shows not entirely different from Eliot’s, though they were known to be quite raucous. These parties were particularly popular in Harlem where rents were high and space was tight, meaning the entertainment often relied solely on a pianist, forcing them to adapt in such a way that the left hand would “stride” percussively up and down the keyboard as the right handled the melody. Over the decades, jazz continued to flourish in Sugar Hill and the rest of Harlem. During its heyday, when uniformed operators manned the elevator and doormen with epaulets escorted residents into the lobby, Eliot’s building was home to many artists and prolific jazz musicians. There was big bandleader Count Basie, for whom Eliot’s corner of Edgecombe is co-named, as well as Cootie Williams and Johnny Hodges, both members of Duke Ellington’s orchestra. Even Ellington himself is said to have lived there. Esteemed jazz bandleader Andy Kirk was also a resident: It was he and his wife Mary Kirk who helped Eliot score the apartment, having recommended her to the landlord. “We were always up [at their place] getting piano lessons,” Eliot reflected on the couple one afternoon. “All the kids studied with them. In fact, I have a sheet of the book—you know how you keep books and stuff—where Mary would give the assignments and so on.” The neighborhood itself was full of music, air thick with melodies drifting out of what Eliot described as live venues and juke joints on every block. It was the perfect location for her—a young pianist, singer, and actress who played gigs all over the city from the Upper East Side to the West Village. In addition to her music, Eliot also appeared in several plays, including the original 1969 cast of the off-Broadway play No Place To Be Somebody, the first by a Black playwright to win the Pulitzer Prize. In the decades since Eliot moved in, most of the neighborhood’s live jazz venues have shuttered. There are still a few spots to catch a show in and around Sugar Hill—most notably, Hamilton’s Bar & Kitchen on Friday nights and the Ralph Ellison Memorial on Sundays during the summer, both organized by Berta Alloway. But Eliot’s parlor is one of the few remaining venues fully dedicated to jazz. On one particularly hot Sunday in June, Eliot’s apartment filled with about 50 audience members. There were a handful of Eliot’s friends, tourists from India to Australia, and other first timers from New York City’s boroughs. Regulars were mingling too: There was an elderly woman dressed to the nines and a young opera student who excitedly explained to me how she had recently fallen in love with jazz vocals. Bodies spilled into the hallways from the living room and kitchen, seated on benches or leaning against walls. It was 95 degrees and the only thing keeping us cool was an air conditioner perched in the window. Eliot’s band passed out cold water and flyers advertising an uptown arts stroll for us to use as fans. Everyone dutifully passed them down until we each had one, fanning ourselves, fingers damp from the sweat of the water bottles. The musicians were sweating too, and they paid tribute to the heat in the set list. Guest vocalist Trané N’Chel was invited up to sing “Summertime,” followed by a group rendition of “When The Saints Go Marching In.” Eliot nodded at her musicians and directed the rhythm from her place at the piano, her face obscured by wide-brimmed sunglasses and a blue medical mask. When N’Chel’s friend hopped up from behind me to join in, filling the room with her booming alto voice, the energy became infectious. People were laughing, swaying back and forth, and clapping to the beat. N’Chel urged them on, dancing with the front row, hands clasped with theirs. As I looked around, I was reminded of something Polatnick had said to me in an interview prior. “Even if you’re uncomfortably sitting behind a wall or in the kitchen, you’d rather be in the parlor. Even if you’re in the hallway outside the door, you still know that you’d rather be there than anywhere else when this is happening. There is no way to get what she’s offering, because it sincerely just doesn’t exist anywhere else.” It’s no secret that intimate venues like these have become few and far between. Jazz itself has declined significantly over the past 100 years: Ongoing reports from the National Endowment for the Arts indicate the number of people who attended at least one live jazz show in the past year has decreased from 12 percent in 1997 to 6 percent in 2022. Even Harlem, whose streets were once dotted with dozens of clubs, now holds only a handful of spots dedicated to jazz full time. Over the years, musicians, journalists, and fans have all asked themselves the same question: Is jazz dead? While some say yes, others have argued that it has undergone a transition like many other canonical forms of “high art” such as opera or classical music. Kevin Fellezs, associate professor of ethnomusicology at Columbia University, described this transition as the “museumification” of the art, a form of recognition and institutionalization in the upper echelons of American culture. “If you think of Jazz at Lincoln Center, that’s kind of the institutionalization of this long discourse, and of promoting jazz as an art music and not just as a commercial pop, dance-oriented music,” Fellezs said. Fellezs in part attributes this museumification to the rise of bebop, a form of jazz homegrown in Harlem and distinguished by its fast, harmonically complex rhythms and heavy improvisation. One pioneer was saxophonist Coleman Hawkins, who was also a resident at 555 Edgecombe Ave. Hawkins completely disrupted the genre in a 1939 recording of the swing standard “Body and Soul,” shocking listeners as he pushed the limits of his craft by playing twice as fast, the melody barely recognizable in the complexity of his improvisation. Inspired by this recording, musicians like Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, and Thelonious Monk took up his techniques in jam sessions and underground spaces, leading to the development of a new style that would go on to eclipse all others. The emergence of such a complex and innovative new sound set in motion a shift in jazz music away from more danceable forms like swing, taking what was formerly considered entertainment or dance music and redefining it as high art. “If you listen to those early bebop recordings,” Fellezs said, “and you listen to what’s considered mainstream or commercial jazz at the time, they’re light-years away from each other. And so it makes a really strong case for yes, there’s something very sophisticated going on here, and worthy of intellectual analysis and all of that.” As bebop took jazz to new heights—claiming space in ritzier venues and historically white concert spaces like Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center—many of the genre’s more intimate venues and informal spaces, particularly where younger musicians honed their craft, were lost. “To play, you need a place where you can do it, you know?” Eliot said. Back in the day, she continued, “there were jam sessions everywhere where people were exchanging ideas. It’s not there [now]. The real estate is not there. You know, places to do it really. So, that’s a hardship.” Although Eliot’s parlor jazz is not a jam session open to newcomers, but rather a curated two-hour concert, it does provide a consistent space for band members to play on a weekly basis and learn from one another, as well as the guest artists who often join the group. Nick Mauro has been playing trumpet in Eliot’s parlor for 12 years now. The two first met when he was 26, fresh out of graduate school and teaching music at a school in Harlem. Mauro said the steady weekly gigs and ongoing stage collaborations have been some of the greatest influences on his growth as a musician. “She will play a lot with form and melody and switch things around just on a whim. So I think the spontaneity of playing with Marjorie really often will keep you on your toes. And in a really good way,” Mauro said. On the one hand, the museumification of jazz has been a good thing, said Fellezs. Its prominence in elite venues, its scholarship at Ivy League universities, even the dedication of entire museums to the genre, all point to a recognition of Black music as a respectable art form—in part achieving one of the key goals of the Harlem Renaissance. Around the world, it is considered one of America’s greatest contributions to art and culture. But the ensuing commercialization of jazz’s elevated status has also meant the loss of certain aspects which once distinguished it. For one, it has largely lost its original audience: young African Americans. Perhaps linked to this shift is the decline in accessibility. You can still find the occasional live show at your local bar or restaurant, but the city’s busiest and most renowned clubs like Blue Note or Dizzy’s Club at Lincoln Center now charge over $45 a seat—though both still offer student discounts—in addition to food and drink minimums. “At Dizzy’s,” Fellezs expanded, “I imagine a lot of those are either tourists who can afford it and have saved up to do their New York jazz travel, or lawyers and doctors and other professionals. That’s kind of the audience for jazz these days. It’s professionals and they can afford to spend a couple hundred dollars to see a band.” But perhaps the most damaging blow has been the one to jazz’s essence. Although few of us may have experienced it, we all have that image in our mind based on movies and stories of what jazz used to be: intimate, spontaneous—a smoky room of musicians, artists, and fans, milling about, sharing in an experience. Marjorie Eliot seems to be one of the few who has embraced a reverence for jazz as a fine art without sacrificing the essence of jazz itself. Eliot has great respect for the form, which she refers to as “African American classical music,” and uses the concert setting to pay tribute to the form’s great composers. But what distinguishes this show from other venues in New York City is that it is intimate and free of charge, allowing anyone, regardless of financial circumstances, to experience the music and connect with one another. The result is clear: There are many young people, the crowd is diverse, and above all, it is alive, making it one of the few places I’ve been where this feeling of closeness and community endures. In the middle of the second show I attended, Eliot stood up during intermission to welcome me back by name. “She’s part of our family,” she told the audience. I was moved by her openness. Although few of us knew each other, Eliot made us feel that we were all part of something. This is what Eliot does. She welcomes people into her home and into her life, and it is not by accident. After Phillip’s passing in 1992, Eliot has weathered the losses of three more sons from various health issues. “After Phillip passed away August 18, 1992, Mikey passed away January 2006. Alfie passed away in March 2018 and Shaunie passed away in March 2023. So [my son] Rudel is here keeping the flame alive,” Eliot said. Hosting these shows is what helped Eliot get through her grief. Not only did it give her purpose—a creative outlet to keep the memory of her family alive, but it also brought her love and community. “You look at the comforting joy and the people who come and I feel this connection, love, and honesty from everybody,” Eliot said. “And I, it just takes me over.” At each performance, Eliot shares her experience and her gratitude with the audience, telling them her story during intermissions and thanking them for the healing they have brought her. That love and collective remembrance for those who have passed was what I myself had felt that first afternoon in the parlor, and that’s what makes Eliot’s concerts so memorable. The mixture of grief and joy can be heard in her music, which oscillates between yearning tunes and cheerful ones like the classic song, “This Little Light of Mine.” “That’s what I mean,” she said, “when I say that this sustaining power of being engaged in my artistry—that you’ll see me sitting there with my sunglasses on because I don’t want tears to drop. And they do come. But playing, and just trying to do it well for them, it’s no showing off, no look at me.” As the show neared its end, the musicians all left the stage, leaving only Eliot on keys. We all watched quietly as the notes trickled out from within the piano, her eyes shrouded behind those sunglasses, body nearly immobile but for the drifting of her hands over the keys. The song was a rendition of “We’ll Be Together Again,” one she used to play with her late son Shaunie. Impressionistic and melancholy, it also floated with a certain sense of lightness, modulating through different scales and tonalities as Eliot manipulated the harmony to offer a glimmer of hope. As she stood up at the end to much applause, she clapped back toward the audience and waited for them to quiet down. “I always say that you are the critical piece of the story,” she said to us. “You’ve taken my story and made something beautiful, and you’ve taken the sadness and lifted it and swapped it in place of courage and love. It’s golden, really. The heart speaks.” Eye Senior Staff Writer Morgan Desfosses can be contacted at morgan.desfosses@columbiaspectator.com.

|

Harlem 135th Street Subway art

Big Apple Jazz Tours private concert for high school students at Parlor Entertainment

Harlem Juke Joint Tour

Your Harlem jazz tour guide customizes the best itinerary for each given night, based on the most talented players in Harlem’s most exciting jazz clubs.

185 Reviews

Harlem Juke Joint Tour

Your Harlem jazz tour guide customizes the best itinerary for each given night, based on the most talented players in Harlem’s most exciting jazz clubs.

185 Reviews

Legends of Jazz Tour

This is our premium tour! It features jazz’s international superstars, and also rising stars who deserve wider recognition.

185 Reviews

Legends of Jazz Tour

This is our premium tour! It features jazz’s international superstars, and also rising stars who deserve wider recognition.

185 Reviews

Greenwich Village Jazz Crawl

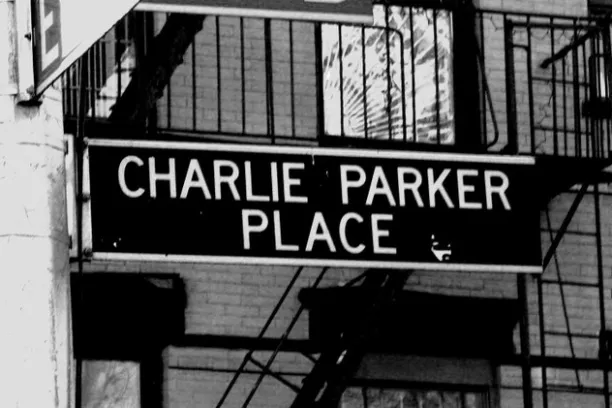

Intimate Greenwich Village Jazz Tour to discover and explore two hidden jazz haunts and the sites where Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, and Bob Dylan made history.

185 Reviews

Greenwich Village Jazz Crawl

Intimate Greenwich Village Jazz Tour to discover and explore two hidden jazz haunts and the sites where Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, and Bob Dylan made history.

185 Reviews

Private Tour

We’ll design your private jazz tour based on your tastes and our extensive knowledge of musicians, clubs and speakeasies throughout the city. We know what is happening nightly on and off-the-beaten-path.

185 Reviews

Private Tour

We’ll design your private jazz tour based on your tastes and our extensive knowledge of musicians, clubs and speakeasies throughout the city. We know what is happening nightly on and off-the-beaten-path.

185 Reviews

Gordon Polatnick

Gordon is the founder of Big Apple Jazz Tours. What started as a personal challenge to discover and document all of New York’s hundreds of jazz joints and to establish Harlem’s first jazz day club, has now blossomed…

Amanda Humes

There’s no one in New York City like Amanda! Equal parts sass, smarts, and customer service – Amanda is the Harlem resident, Columbia University graduate, and…